Ben Arnold’s Continual Search For The Missing Truth

they came from the west

sailing to the east

with hatred and disease flowing

from their flesh

and a burden to harden our lives

they claimed to be friends

when they found us friendly and when foreigner met foreigner

they fought for the reign

exploiters of africa

- Madingoane, 1979.

This essay delves into the politics, philosophy and art that embody Ben Arnold's (b.1942) world amid his persistent search for what he terms the truth. I discuss selected artworks by the artist to help investigate his continual search for this elusive truth. In tandem with various cultural initiatives that started emerging across the African continent following WWII, I set the scene by navigating Arnold's initial studies between 1958 and 1965 at the Polly Street Art Centre in the inner city of Johannesburg. Exploiting Black Consciousness as a philosophy and a way of experiencing being in the world, I explore how Arnold’s early influences helped him develop an intrinsic visual language. In this article, I discuss the artist's selected works tinted with nostalgic memories of a particular African consciousness. My exploration starts with Untitled (Dervish, 1963), a drawing that investigates how Arnold employs representation to interrupt memories of colonial apartheid. To further complicate the artist's quest for his truth through art, I briefly explore Sprouting Form (c.1991), a terracotta which evokes experiences of a particular way of existence. Arnold created the abstract sculpture while working at the Bag Factory Studios in Johannesburg a decade after converting to Islam in 1981. Lastly, to help understand this quest for the truth, I discuss The Lion of Judah (1979) and Pilgrim’s Destination (1988), which I argue represent an exploration of Arnold’s material and spiritual reality. This analysis of works of art investigates Arnold's creative journey over time as the marker of his attempt at making sense of life.

Elucidated in the epigraph, Ingoapele Madingone’s pan-African plea, Africa My Beginning points to the colonial apartheid's project of brutally dominating and uprooting local communities from their lands. This venomous conduct planted anger, discontent and defiance in the young Arnold's mind, hence his continual search for the truth. The pain and embarrassment that emanated from the racial bullying encouraged him to consciously seek solace, belonging and answers to this discourse of racial prejudice within his surroundings. In the process, Arnold initiated and assumed membership in local cultural groupings such as the Soweto Arts Association and Mihloti Black Theatre Council, whose aim included political awareness through the arts. These cultural units networked with other anti-colonial, avant-garde and politically-charged formations such as Dashiki and Mdali to intensify his political consciousness. In an attempt to assert his being, the Johannesburg-born Arnold embraced Mokoena as part of his full name. This consciousness took root in the 1970s while the artist soaked in influences from the world's anti-colonial philosophies such as pan-Africanism, Negritude and Black Consciousness. Encouraging the oppressed to overcome feelings of helplessness, ignorance and self-hate, some cultural organs attempted to disrupt oppression through performance, literary and visual art, as seen in Arnold’s interactions.

A broader look at his body of work reveals a pattern defined by the amalgamation of representational and non-representational sensibilities that started from his days at the Polly Street Art Centre.[1] In 1964, Arnold became one of the artists who emerged from the Polly Street Art Centre to join the stable of the German immigrant and master printer Egon Guenther. Guenther settled in South Africa in 1951 following the division of Germany into the west and east blocks. His love and taste for contemporary European and African art led to a special relationship with the head of the Polly Street Art Centre, Cecil Skotnes (1926-2009). Considering Guenther's vast experiential knowledge, it seems logical that he subtlety influenced Skotnes' modernist aesthetic. In turn, Skotnes' art began fusing European modernist and African art traditions to birth aesthetics, which wrestled with a semblance of the African identity (Koloane, 1989: 215). As a result it became easy for Arnold to follow in the footsteps of his teacher and mentor, who "showed interest and taught me [Arnold] the technicalities behind art (sic)" (Post, 1974, 4). Arnold began experimenting with representations which evoke the African mask (albeit generically), cubist sensibilities, rock and cave paintings. High profile people like Edoardo Villa (1915-2011), Guenther and Walter Battiss (1906-1982), then regarded as the advocate of rock art in South Africa, often visited the centre to share and interact with the artists in training (Miles, 2004, 13, 70). Reading one of Arnold’s early drawings, Untitled, the apparent influence from some of these people becomes noticeable in what appears like a preparatory sketch for one of his sculptures.

This sensitive graphite composition reveals Arnold’s unfolding artistic evolution in a drawing that depicts “a dancer”, perhaps an initial sketch in preparation for one of his energetic terracotta sculptures (Arnold, communication with the artist in 2022, 8 March). This drawing depicts an elongated, half-naked male figure whose back faces the viewer. Arnold portrays the figure without any recognisable extremities. Typical of how Arnold developed compositions in expressive, minimal straight lines, the drawing represents a lonely figure with stretched-out arms as if lost in a mysterious, sensual movement. Reminiscent of Arnold's creative stratagem are the large flat areas which accentuate how light falls at different angles and intervals to mark the passage of time. Also, the contrast between the sensitive strokes against the flat negative space intensifies the figure's sense of dynamism and movement. Arnold created the composition when fear dominated Black South Africa following the 21 March 1960 Sharpeville shootings and its aftermath, such as outlawing political activity in the country, sweeping arrests and forced exile. Instead of throwing hands up in the air to despair, Untitled registers this passive mood of helplessness as a subtle protest against waiting for the oppressor's hand and foot. A precursor to the Black Consciousness spirit that dominated parts of South Africa starting from the late 1960s, the drawing evokes anger, discontent and defiance against apartheid’s normalised reliance on the cheap labour of the oppressed.

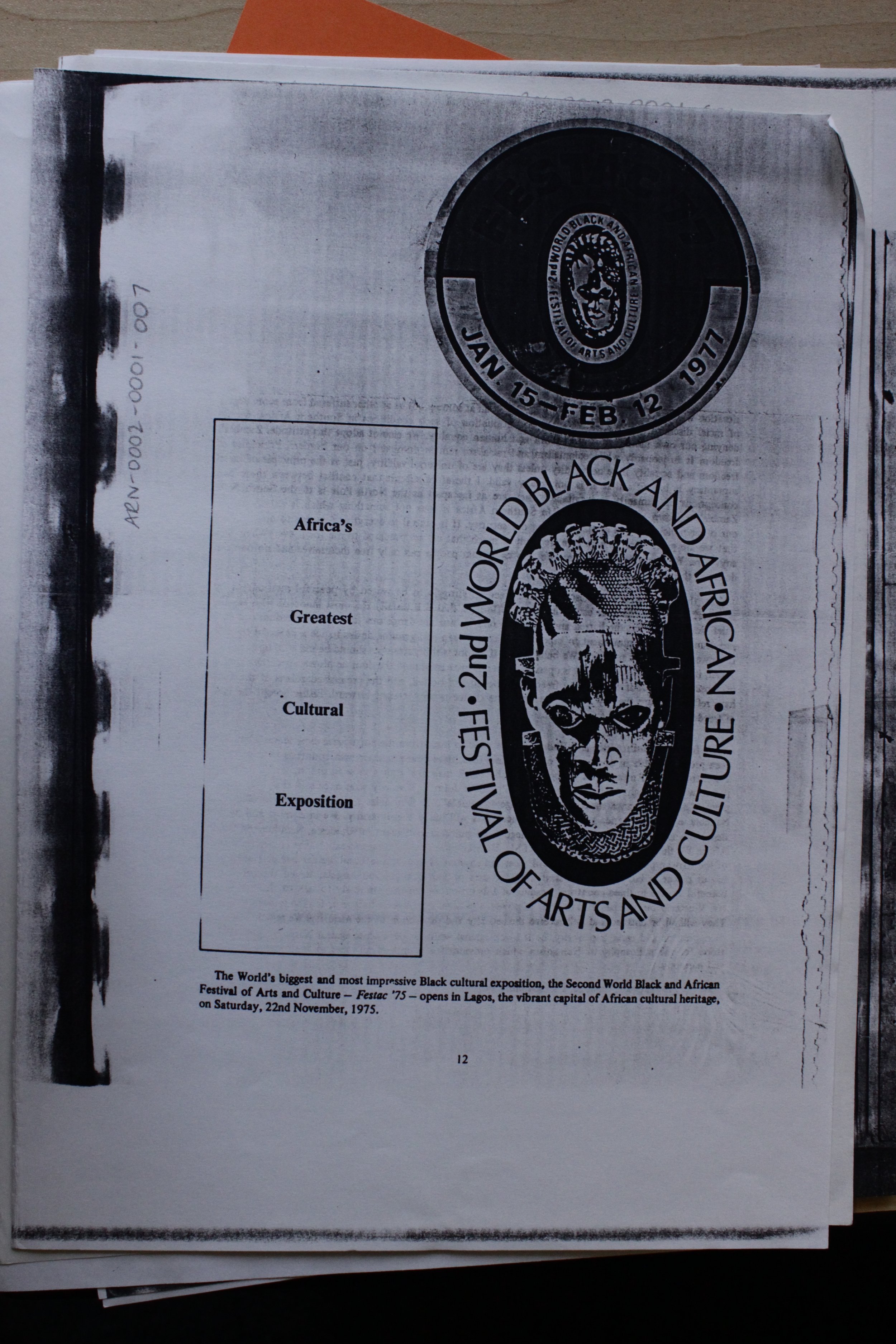

Culturally, the 1970s saw Arnold’s total immersion into the politics of Black Consciousness while participating in various activities often sponsored by its cultural wing, the Cultural Committee (CULCOM). During this time, the artist continually searched for opportunities to engage his cathartic political awakenings through imaginative acts such as stage plays and exhibitions. Arnold became a member of the collectives Mihloti Black Theatre and Soweto Arts Association, whose primary purpose included the interruption of any semblance of normality under apartheid. In 1972 he became a core member of the Mihloti troupe that participated alongside Dashiki at the South African Student Organisation’s (SASO) week-long General Students Council meeting at Saint Peter’s Conference Centre in Hammanskraal (Hill, 2015: 74.). A close reading of the excerpt from 'Africa My Beginning' at the opening of the essay brings to mind how Arnold and his wife, Mmakapa shared similar pan-African values espoused in the poem. Mmakapa grew up under the Madingoane household and interacted firsthand (and by extension, Arnold) with Ingoapele Madingoane, who also affiliated with Mihloti. 1977 saw Mihloti travelling to Nigeria, where the cast experienced 'the world's biggest and most impressive Black cultural exposition' aptly titled Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (Festac '77). Inspired by the Négritude and Pan-African desire to promote African unity, Senegal hosted the first festival in 1966, with Nigeria set to follow in 1970. Instability and civil war (between 1967 and 1970) dominated the recently independent country and halted preparations for the upcoming pan-African jamboree. The Nigerian composer and activist, Fela Kuti boycotted and held a parallel event at his Kalakuta shrine after an illusion of peace allowed time for the festival to happen at the start of 1977 (Moore, 2016: 117, 119.). Courtesy of the Swiss International University Exchange Fund (IUEF) and under the auspices of Mihloti, Arnold and Mmakapa became part of the nine-member uninvited South African delegation that participated in the fringes of the official programme (Pheto, 2020). Meanwhile, in South Africa, 1977 proved bloody, as seen in how apartheid savagely dealt with its opponents. Recall that many young people died following their courageous rebellion against the state machinery the preceding year.

Similarly, Arnold continued wrestling with ways to disturb the dominant colonial-apartheid machinations, remnants of which continue to wreak havoc into the post-1994 dispensation. The artist created a cheeky terracotta, a Black Consciousness-inflected composition, which foregrounds the African narrative. Arnold's creative processes aim to spread knowledge as they cohere in the sculpture, The Lion Of Judah. The small composition asserts the late 1970s mood and resolve to push back against oppression. The work evokes images of a pan-African worldview through its subject matter and title. It depicts a stylised and robust male lion sitting on its rear end while its fore paws rest on the ground. Erect, bold and ready to charge, the lion's mane evokes images of the Dakota Sisters' Muskmelon with its repetitive burrowed patterns that frame the vague face. Arnold deftly depicts the wild cat looking obliquely into the sky through straight lines that suggest its massive paws, nostrils and eyes. The Bible book of Revelations 5:5 points to the lion of the tribe of Judah as Jesus Christ in contrast to Arnold's sculpture, which points to the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I. Selassie assumed the title of the Conquering Lion of Judah after his ascension to the throne as the emperor of Ethiopia in 1930. A decade earlier, the pan-African Jamaican political leader Marcus Garvey urged his enslaved and oppressed compatriots in the Americas to look to Africa for a king who would emerge as their redeemer (Grant, 2020: 114). Garvey’s message spread throughout the globe in countless lyrics from reggae sounds, which dubbed Selassie the Black Messiah. To help capture the empowering spirit imbued by Selassie, Arnold interpreted his composition, which depicted the lion as an able, affirmative agent of courage and strength. In 1962, Ethiopia under Selassie hosted Nelson Mandela, who underwent military training before his incaceration in Robben Island and becoming the first democratically-elected president of South Africa in1994. Ethiopia coodinated the 1963 meeting under the leadership of Selassie to help establish the geopolitical Organisation of African Unity (later named the African Union) in 1963 (Mandela, 1984: 283, 292-294).

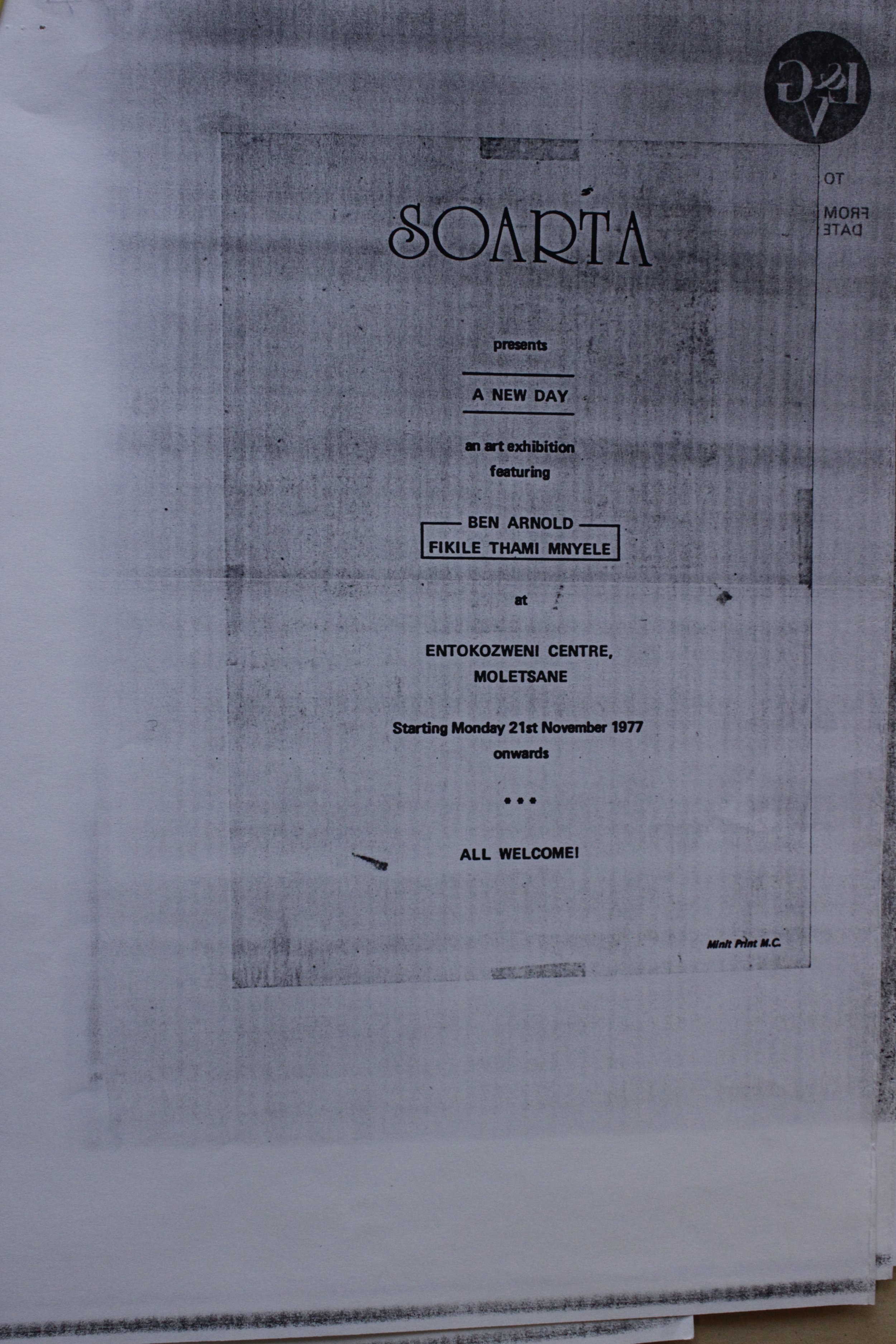

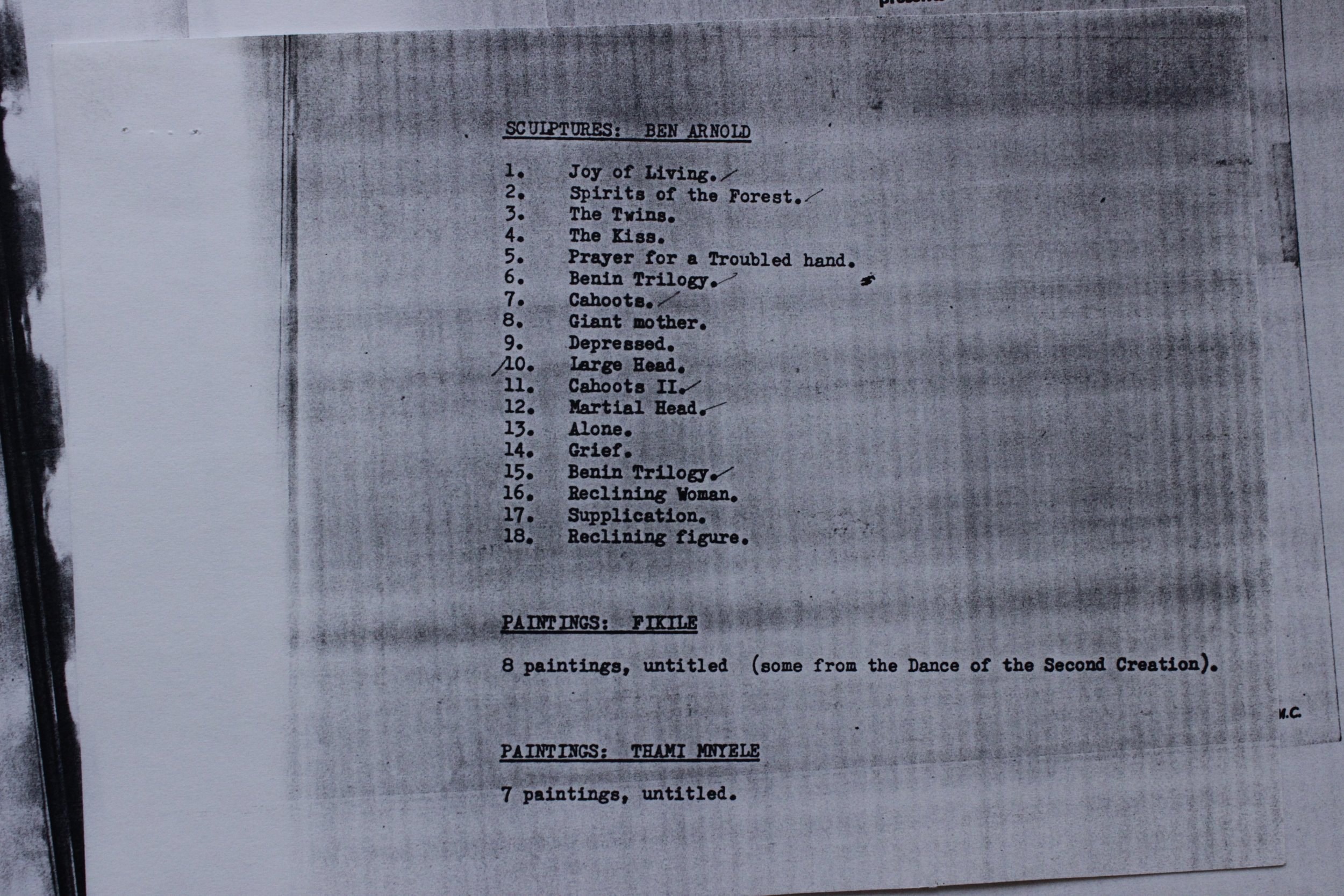

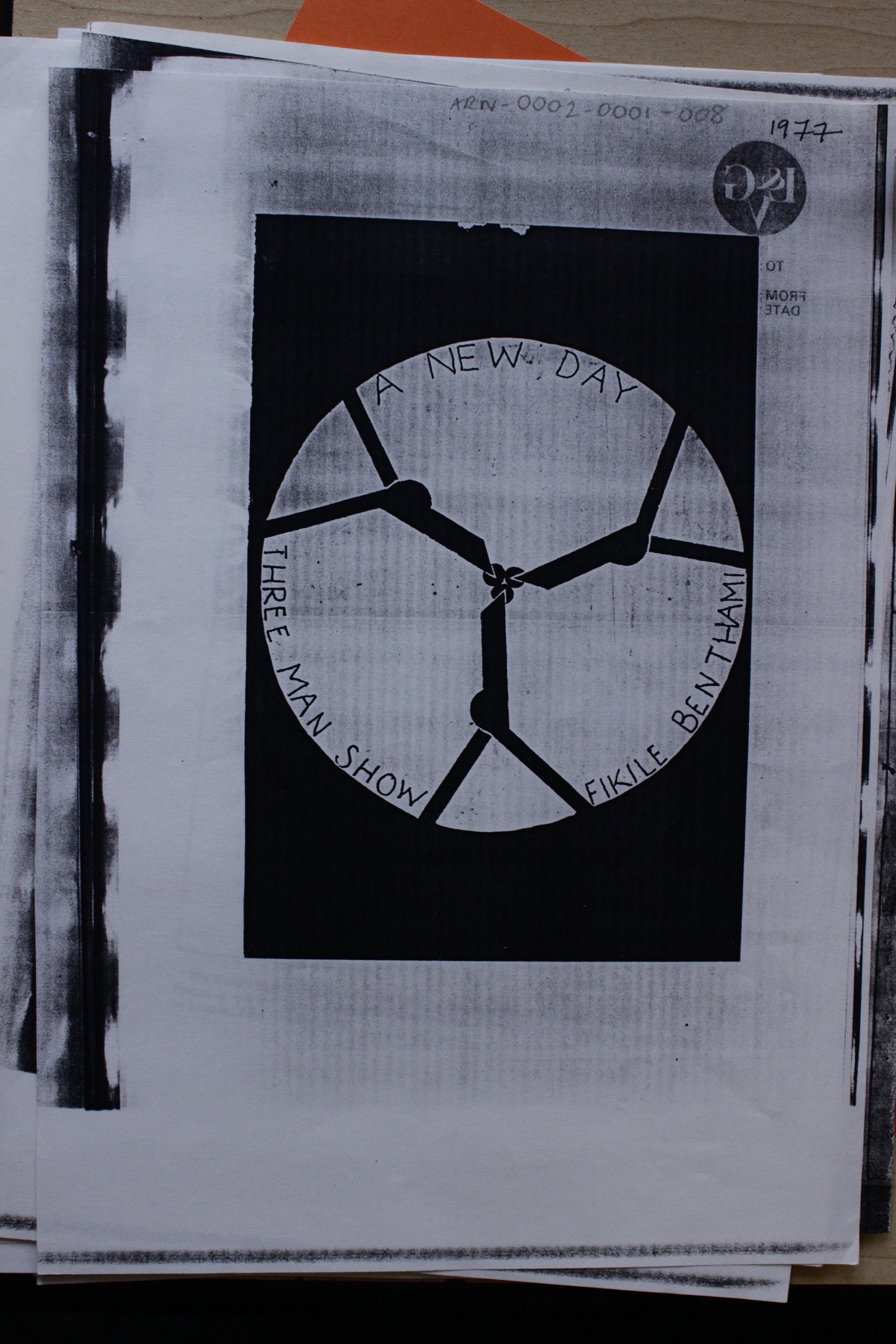

Ben Arnold personal archives including a 1977 exhibition with Thami Mnyele and a Festec (Second Festival of Black Arts and Culture) pamphlet that was held in Lagos also in 1977. Photographs by the author. 2021.

The year 1977 proved eventful in South Africa, three days after the brutal murder of Steve Biko in police detention, Arnold, Thami Mnyele (1948-1985) and Fikile Magadlela (1952-2003) exhibited sculptures and paintings in the travelling exhibition A New Day. In the exhibition, Arnold demonstrated his pan-African outlook and hope for better humanity in titles such as Benin Trilogy, Spirits of the Forest and Joy of Living. The exhibition toured venues such as YWCA (Young Women's Christian Association) in Dube, Entokwezeni Centre in Moletsane, Donaldson Orlando Community Centre in Orlando East and Regina Mundi in Rockville in Soweto. One of the exhibiting artists, Mnyele (1980:42), remarks about the exhibition held at the YMCA:

So our exhibition was attended by thousands of people. In South Africa, as far as I know, not many people attend exhibitions, especially not people from the black sector. We had people standing at the door counting and there were more than a thousand people crammed into the place and there were more waiting outside.

Although already showing his art in group and solo exhibitions globally, Arnold claims A New Day helped him discover and embrace his Blackness. Arnold insists the exhibition attempted to project the exhibiting artists' "vision of a free Azania... aligned to the ideology of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC)" (Arnold, communication with the artist 2022, 8 March). I set Mnyele's commentary about the exhibition in the context of apartheid's divide, rule and conquer strategy. This way of seeing life encouraged people to forefront their perceived racial and ethnic differences. The strategy infiltrated the material experiences of daily living as the residential, recreational and employment spaces followed its strict pattern. That being so, the exhibition managed to communicate its message of emancipation to audiences whose dynamic voices continued challenging the white supremacist's simulated invincibility it maintained through savage laws and policing.

Amid apartheid's brutality in the second half of the 1970s, the Black Consciousness philosophy managed to articulate the experiences of the oppressed in a process that led to the 16 June 1976 students' uprisings. The resultant state retribution and violence against the oppressed begot more carnage into the effervescent cauldron of the 1980s. The Black Consciousness thinking encouraged liberation "for we cannot be conscious of ourselves and yet remain in bondage" while responding to the call to render the country ungovernable (Biko, 2004:53). This manifested through the physical establishment of self-defence units, community courts and the United Democratic Front (UDF) among others (Battersby, 1994). Let alone the violence of the period, Arnold continued teaching art to young people while his visual imagery strove to reflect Black Consciousness thinking. For some time, his association with like-minded individuals seems to have translated his pain and resentment into an affirmative, creative avenue filled with a positive outlook on Blackness. As a constant thinker with a limitless quest for the truth, Arnold's restlessness led to converting to Islam in 1981 and adopting the name Abdus Samad. Samad seems to have withdrawn from public art life while his work veered towards abstraction. Samad qualifies his conversion to Islam that, "growing up in Albertsville, I had Muslim friends who introduced me to the faith and often let me go with them to the madrasa " (Arnold, personal communication in 2023, 8 March). A generally figurative artist up to this time, Samad says Islam "led to my discovery of the truth that there is no one but God and that Christianity is the source of colonialism" (Samad, personal communication in 2023, 8 March). The conversion seems to have impacted Samad’s worldview and mode of representation while shifting his search for the elusive truth to organised spirituality.

Towards the collapse of the official apartheid and the unbanning of political activity in the country, Samad asserted his resolve in the power of Islam by depicting what I consider a romanticed version of his truth. He created a low relief composition to represent a stable modern architecture suggestive of the holy city of Muslims in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, titled The Pilgrim’s Destination. This horizontal structure comprises five rows of four panels depicting the city at the top half of the image plane. A cubic square in the middle of the work interrupts what looks like a mosque in the background. On closer inspection, this cube with vertical columns looks like "the Ka'ba, a huge black stone house in the middle of the Great Mosque", that Malcolm X witnessed on his visit to the city in April 1964 (Haley, 1965: 450). Known as Hajj, this pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in the lifetime of a Muslim who can afford it, is a religious obligation. Samad expresses this ideal in a majestic composition covered in red oxide, as does most of his other sculptures. This solid composition asserts the importance of his new faith and belief in the power of Islam as the bearer of the truth.

During South Africa's political transition from apartheid in 1991, Samad took a studio space at the Fordsburg's Bag Factory Studios, where he kept a kiln to fire his terracotta compositions. He sculpted the 'Sprouting Form.' This sculpture divides its top part with decapitated horns and a stout lower part supported by four short legs. A polygon of protruding and severed horns forms what looks like a crown. Samad's abstract composition brings to mind a violently interrupted kingship and a particular way of life marked by the soil. The sculpture evokes images of rock art with disproportionate representational figurines lost in a hypnotic state. In a general sense, horns connote power, militancy and resistance to external forces, and the Sprouting Form’s severed horns may suggest an interruption of personal agency. Samad's sculpture points to the sprouting of new horns of the belitled indigenous San community amid the political changes in South Africa during the tumultuous 1990s.

Currently, the artist's creations comprise recycled objects which reflect his advanced way of seeing the world, the ongoing understanding of Islam and visual communication. Again, Samad's image-making includes found plastic bottles, bottle tops and cardboard to birth compositions engulfed by eerie disposition. The spookiness emanates from a creative intervention that follows shapes, colours or textures of objects to determine the represented abstract visual form. A close reading of where Samad's work started bears testimony to the evolving nature of his search for the meaning of life reflected in his visual art forms. Fixing one's gaze at the artist's body of work from the early 1960s to the present resonates with questions asked, Sower Of Words (2006). In the song, Vusi Mahlasela and Dave Mathews pay tribute to the poet, Ingoapele Madigoane by provocatively asking how the passage of time has dealt with pan-Africanism. Apparent in its adherence's state of material being, Mahlasela and Mathews complicate Madingoane’s Africa My Beginning by asking,

In what realm of Africa are we at this point?

Africa the beginning, or Africa the ending?

The song vivivdly depicts Madingoane moving from one shebeen to the next in search of pieces of poetry during the last days of his life. On the other hand, Madingoane's contemporary, Samad alternates between the mosque and his home studio to illuminate spiritual awakening. The Sower of Words raises questions about the material reality of actors of the pan-African project while evoking memories of creative souls such as Lefifi Tladi (b.1949), Ike Nkoana (b.948), Samad and Madingoane.

In conclusion, although obscure and generally unknown in the present, Samad has been active as an artist since the 1960s with his contemporaries, including luminaries such as Louis Maqhubela (1939-2021), Ephraim Ngatane (1938-1971) and Lucas Sithole (1931-1994). In the first instance, the themes of his representational terracotta sculptures asserted the African continent through titles and subject matter that evinced his worldview. Samad's angular compositions, marked by planes of dominant large, flat areas, interpret the dynamics of tonality. Samad's constant search for life's meaning drives an artistic career that spans over five decades of interacting with spatially racist surroundings. In the general run of things Samad's life and art move between African and spiritual consciousness as he continues to search for life's meaning. The fact that the artist is relatively unknown and seemingly ignored in the country of his birth complicates this quest for the truth.

[1] In “Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity,” Associate Professor of English at the University of English, Elizabeth DeLoughrey offers new modalities of reading oceans and their haunting of literary imaginaries. DeLoughrey suggests that “heavy” water is a sign of an oceanic stasis that signals the dissolution of wasted lives. This heaviness is apparent in Lorde’s poesis, wherein the waters of the Pearl are trusted to dissolve Emmett Till's wasted life.