Return Interrupted

Prologue:

The call to “return” for descendants from slavery back to the continent of Africa is a curious one. The- Back- to- Africa movement or Garvey-led ideologies make a call to return to the continent of Africa for all those who descended from slavery as a means of repair and refutation: Repair as in mending the bonds between peoples violently separated and sold through the trade and those who never left. Refutation as in refusing to capitulate to the aims of colonialisation and reside and build the worlds of the West.

It’s a question and quest that attempts to bridge a gap that is 400 years old, 500 hundred years wide, and was forged by inexplicable horrors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Return has been intertwined with Pan-Africanism, a movement that has sought to repair and engender means of connection and world-building between Africans and all those who descend from the continent (Shepperson, 1962). However, altruistic political movements equally have the capacity to coopt and recreate the exact harmful structures they insist to oppose, recast with preferential characters.

When looking at the past one hundred years, return and connection have been practised through various conferences and convenings, where large gatherings of artists, intellectuals, and cultural workers gather over days or weeks to debate, discuss, and exchange along the lines of culture and politics. While grandiose and intuitive in design, they did not always dismantle power structures but reified the power dynamics that have been put in place by colonialism along the lines of hegemony and proximity to empire.

Perhaps one of the longest-lasting and contemporary convenings is ‘The Year of Return’ Initiative launched in 2019 by the national government of Ghana, in partnership with Diaspora Affairs, also within the office of the president. The Year of Return welcomed “home” all those who were taken into slavery and descended from the continent and held a year of programming including cultural events and political discussions. However, during the Year of Return and my own experience of Accra in its aftermath in 2024, there is an uncomfortable fusion of “worlds”, where global north standards have influenced and gentrified established and local traditions, prices, and significantly, land ownership.

The year-long programme, while undoubtedly a catalyst for exchange and business in Ghana, underscores a more concerning reality. It reveals how the notion of return can often bypass the very people it ostensibly seeks to connect with. The influx of Western Black individuals gaining access to property, land, and government officials, while local Ghanaians grapple with skyrocketing living costs, paints a picture of gentrification that mirrors structures of colonialism that have displaced communities and peoples for hundreds of years. Return and connection for who?

Overarching, returns did not and do not happen without internal debate, power dynamics, and stratification along lines of gender, sexual identity, nationality, class, and proximity to imperial power, sometimes widening the gap that was created by the door of no return. Ultimately, “return” raises critical questions about who truly benefits from initiatives aimed at fostering connection and growth.

Return Interrupted explores the ways that the idea and practice of return is easily ruptured, even as the contemporary logistics of “return” are straightforward, and increasingly, advertised in countries like Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa.

This piece honours the history of repair but does not discount that harm, especially in the form of patriarchy,which is rife within political and cultural movements, and in our society and world broadly. This piece critiques notions of return that are surface-level, and further propel practices of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism under the guise of reconnection.

Finally, I explore a reconfiguration of this six-letter word that hinges on understanding one’s personal freedoms; one’s own reflection in order to see another for a person and not an assembly of answers to one’s questions.

Return Interrupted

When you want to “return” as a Black person, you first enter through metaphor.

Metaphor ties a lasso around what you can see and what you imagine and tightens the knot around your physical body, to bring you closer to the complete abstract, and the very unknown.

It makes you an assembly of speculation, and ‘gathers you’ (Morrison, 1987). Sometimes the knot asks questions, other times, it repeats cliches:

An old pair of shoes that no longer fit.

An Olive tree that grew in your absence.

Milk that was left out on the shelf and spoiled so terribly.

The farm overgrew itself. Moss grew over the atrocity.

People had babies on the land made available from the paving of mass graves.

A reflection fractured in water that will not sit still because of the waves and fishing community that uses it daily.

Returning is a process riddled with unanswerable questions once you’ve cycled through the metaphors. You may only form questions based on what you can see, and what you believe.

For example, I was sitting at lunch earlier this year while at a residency in Accra, and it had been dark and storming all morning. As we sat down, we heard roosters start to crow; one friend jokingly said “You’re late”, directed at the roosters, and another friend said, “They believe what they see”. They believed that it was morning and not midday. They believe what they see.

Do you also believe what you see, and imagine what you cannot?

Returning entails asking questions that grasp what the eyes can see, what the sensibilities can guess, and what you may feel. And asking that question may result in an answer that doesn’t satisfy.

Photo: Fort Prinzenstein dungeon courtesy of the author

Dionne Brand (2002) says, “When you embark on a journey, you have already arrived. The world you are going to is already in your head” (p. 71). When you ask a question, you know the answer. You know that you don’t know, but want to. You know you want to piece together why something sounds a certain way or find out why someone does something a certain way.

Why do you turn your head to the left? Why are funerals like this? What is the psychology of any given language in West Africa and how long will it take you to learn it all? What if the answer doesn’t always have a 500-year answer or remedy?

Returning 500 years later to the aftermath of the transatlantic slavery trade is returning 500 years late. And 500 years isn't just aftermath. Maybe to some of us. But not to the people whose stories were never bound up in the “leaving”.

In the case of diasporans, we return in different ways. For those of us who lost some connection to land, language, food, etc. hundreds of years ago, rather than one generation ago, I am trying to tell you a story and illustrate that this thing has happened and is no longer happening in the same ways, and you have a little more agency than before.

What happens when returning wears the suit of colonialism, and there is no other language to speak besides English and all its violences? What happens when you meet the eyes of discontent and annoyance upon your return?

While you may be concerned with the past, many others are antagonised by the present.

What happens when you realise you cannot account for the 500 years? What does return mean and does it have to involve a single question and a single answer, land and acceptance? Most of us want to see for ourselves. I know you want to see for yourself. So let's see.

Return Romanticised, Tried, and Tested

In hopes of connection and “return”, the contemporary canon of Black and African arts and politics from the 1950s and onwards (though Pan-Africanism has been practised as early as the late 1800s), tells a story of conferences and festivals. At these varying conferences, thought leaders, artists, musicians, writers, thinkers, teachers, and students were in attendance in various places of the world trying to bridge our “gaps” created and sustained by the trans-Atlantic slave trade and colonialism.

The political aims of return movements are deeply intertwined with shared pathos amongst Diasporans. For example, major tenets of Marcus Garvey’s Back-to-Africa movement were underpinned by political unity as well as a deeply emotional drive to restore dignity to those who had been subjected to the atrocity and humiliation of the transatlantic slave trade. Return offered redemption, “How dare anyone tell us that Africa cannot be redeemed, when we have 400,000,000 men and women with warm blood coursing through their veins?” (Garvey, p.7). What often sits next to the strive for redemption is the demand for complexity and a plethora of questions: Does a united Africa guarantee dignity for every kind of Black and African person? Are nation-state structures that can ensure that? Once geographically united, is the project of return and the two divided “sides” complete?

While these return-centred events function to affirm that reconnection can happen, they also externalise the ways the door of no return remains ajar between us (Brand, 2002). The First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists of 1956, at the Sorbonne in Paris, France presented serious questions about connection beyond everyone sharing African ancestry, beyond being Black, African, and othered by the white world.

James Baldwin, the civil rights activist, artist, and observer at the conference, penned Powers and Princes for Encounter, a CIA-backed journal (unknown to him at the time, and a common occurrence throughout the 1950s, 60s, and 70s) where he discussed, at length, the kinds of contentions that emerged.

Photo: First World Congress of Black Writers and Artists, September 1956. Citation: Horace Mann Bond Papers (MS 411). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

There were clear divides that demonstrated that colonialism and slavery have transformed some of us beyond a “return”. Scholar and professor Caryl Phillips, highlighted in the documentary that centres on the Congress, Lumières Noires, that, “The americans were americans before they were Black. They were not there as victims of colonialism like Césaire, Lamming, like Diop. They didn’t feel that they had been born in the crucible of colonial oppression” (Lumières Noires, 2016).

A long list of conferences and festivals followed this Congress including: All African Peoples Conference in Ghana, 1958; The Second Congress of Negro Writers and Artists in Rome, 1959; Festival Mondial Des Arts Négres 1966 (The First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar 1966; The Pan-African Cultural Festival held in Algiers in 1969; Zaire ’74; and perhaps most well known and largest in scale, FESTAC 77- The Second World African Festival of Arts and Culture in Lagos, 1977 (Rosen, 2023).

These conferences affirm that we, Africa and its diaspora, have met, travelled across murky waters, performed, spoken, disagreed, and gained deep understanding. What also reveals itself out of these conferences and the work of their attendees is that we have been having similar conversations each and every generation. Negritude and Pan-Africanism, culture and politics, returning and remaining, and communism and capitalism have dominated our canons. Still, one has to dig deeper for more intimate forms of liberation which often get lost in the flash of “big questions”.

Return interrupted by patriarchy

“Therefore, Black internationalism, as Edwards suggests, contains (and sometimes

suppresses) a narrative of the emergent feminism taking root among internationally and

upwardly mobile women of African descent.” (Bagneris 2011, pg. 8)

Returning has not only incurred a sense of augmented imagination and wonder but an augmented power dynamic where Pan-African and Post-colonial leaders and presidents are remembered as a canon of men. Patrice Lumumba, Aimé Césaire, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, Kwame Nkrumah, Kwame Toure, Chinua Achebe, Amílcar Cabral, Steve Biko, and of course, Frantz Fanon often decorate the 101 curricula of African and Black Political thought.

However, Black and African women and queer writers have documented and theorized about their omission, their experiences of harm, and long-lasting legacies of patriarchy. This illuminates selective and erroneous iterations of ‘liberation’ that retain colonial byproducts of homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and imperialism:

In 1979, Michelle Wallace wrote, to much controversy and public dismissal, (Staples, 1979), “Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman”. In this text, she deeply criticised the Black Power Movement and its leaders for their patriarchal underpinnings and veneers of charisma. This overvaluation of power being defined as the ability to exert force over another results in the epistemic erasure Black women’s contributions, and importantly leadership, to racial justice movements,

“Perhaps it was necessary for Huey Newton and the Black Panthers to make a public display of arming themselves. Their actions represented an unprecedented boldness in the sons of slaves and had a profound and largely beneficial effect on the way in which black men would regard themselves from then on. Yet the gains would have been more lasting if an improved self-image had not been so hopelessly dependent upon Black Macho—a male chauvinist that was frequently cruel, narcissistic, and shortsighted” (Wallace 1979, pg. 68).

Nikki Giovanni in a popular conversation with James Baldwin infamously said “I don’t like white people and I’m scared of Black men” (James Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni, 1971).

Makhosazana Xaba (2013) wrote in the title story of her collection, Running and Other Stories, about an ANC delegate who is confronted with another comrade “in the struggle” who sexually assaulted her. This is an all too common story, fictional and literal.

Famed Kenyan writer and Pan Africanist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was revealed to have abused his wife, Nyambura Ngũgĩ. This was shared on X, formerly Twitter, by his son, Mukoma Wa Ngũgĩ, who shared that this abuse informs his earliest memories (Wa Ngũgĩ, 2024).

Post-independence nations and former colonies like Uganda and Jamaica possess an imported homophobia and transphobia intricately intertwined with colonialism and missionary religion, propped up by gender roles that dictate who has power and who does not (Wahab, 2021).

Throughout our returns and respective moments, the abuse and omission of women, femme people, and queer people takes up the negative space. When fighting for freedom, seldom is it warned that you may experience liberation speeches in the day, and assault at night by the speaker.

Beyond the harm in political spaces that impedes visions of justice and liberation that are truly world-defying, women writers, leaders, and organisers are often buried deeper in the canon, sometimes lost and disappeared, alongside the knowledge produced that disavows romantic versions of political and arts movements. The organising work of Lady Oyinkansola Abayomi, Charlotte Maxeke, Ruth Neto, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Margaret Ekpo, Adelaide Casely-Hayford, and the academic and creative work of Maryse Conde, Awa Thiam, Mabel Dove Danquah, and Efua Sutherland and the legacies of many more task us with creating possibility as much as we are covered in it.

Further, the work of people like Ama Ata Aidoo, Mariama Bâ, and Bessie Head are less sung as major contributions to liberation on the accounts of gender discrimination and the undervaluing of fiction as a viable liberation strategy.

What novels, plays, short stories, and music offer is indeed liberation lessons, if you are looking for them.

In Our Sister Killjoy, Aidoo writes Our Sister with care for dignity, but it is not dressed in a beret or soldier’s uniform. Our Sister Killjoy, or Sissie, is a student from Ghana studying abroad in Europe contending with the lived experience of being received as a spectacle at times and at others, misunderstood and misread. Sissie’s narrative isn’t dominated by one-dimensional assumptions on what being a Black woman must be like, or ruminate on racist spectacles. Our Sister is inquisitive, contemplative, observant, and honest about the unbelievable exhaustion that comes from trying to pursue justice, and under the discussed component of “the work”,

You are saying, There goes Sissie again. Forever carrying Africa's problems on her shoulders as though they have paid her to do it. I am ashamed of these preoccupations Because you were always trying to get me to realise that the faults indeed are too old and they have sunk too deep into the fabric of our lives to be corrected in a day. That is, even if we were to start doing something about them immediately. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like we are ready or anxious

to. (Aidoo 1988, p. 118)

Photo: Our Sister Killjoy book cover

Sissie and characters like her offer the deeply needed humanistic reflection of what commitment to justice looks like, and what our own commitments look like. Perhaps most importantly, Aidoo’s writing affirms that those personal definitions are the most important ones. At the end of our days, we do not always have principles- we have decisions to make, mouths to feed, applications to be written, dreams to nourish, grief to tend to. Political theory cannot always offer a hand after it has sparked a fire.

Of course, the mere presence of women and/or femme people is not enough evidence of criticality or inclusion.

Rather, the consistent absence of certain kinds of people is evidence of a sustained power dynamic that privileges educated men and generalises mankind to humankind.

Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí historically interrogates this via import of gender on the continent, focusing specifically on Yoruba societies in Nigeria. Oyěwùmí antagonises gender by illuminating its fallibility, its inability to “fit” Black people and cultures, its colonial and religious roots, and the division of human beings into categories that become legible to the state and ultimately to patriarchal power systems. As a result, the category of “woman” is reinforced through social othering, sexual violence, and binary meaning-making systems.

Oyěwùmí (2005) also argues that there is no grand difference between gender and biological sex. In our contemporary politics, we often distinguish gender as socially constructed and therefore malleable and performed and biological sex as scientific immutable truth. She argues that they are on the same side of the coin as both essentialise difference.

Difference, as Stuart Hall (1997) notes, is fundamental to whiteness. Binaries exist to simplistically deduce not only what is good, moral, correct, and beautiful, but equally what is wrong, criminal, inferior, and ugly. The reduction of personhood into gender that privileges maleness and whiteness presents an abundance of issues for Black people who have been deemed by the binary as inferior and un-human.

The power Black men seek to hold and are constantly denied holds a legacy through slavery, colonialism, and our struggles for liberation that tend to struggle for Black people, but render women and queer people second, third, fourth afterthoughts, if thoughts at all.

Feminist and humanistic interventions can push us beyond the question or wonder of return, and orientate us closer to the practice of recognition and reflection of one another. The need for liberation often starts with oneself and not with the reformation of a state or a punitive societal structure. The aim of return can be more intimate and less literal, all-encompassing, and ‘unanimous’ in the eyes, words, and actions, and art of Black and African feminist figures.

Our “returns” are just as plagued by an inability to see past binaries as they are by the omission of women’s and queer peoples’ experiences and creative and political contributions.

Return interrupted by the CIA and IMF

While diasporas globally have developed a geographical or spiritual affinity for varying parts of the continent (the americas and Ghana, Brazil and Nigeria, Jamaica and Ethiopia), the governments or former colonising powers have capitalised on that affinity.

One of the greatest examples of this is the US. The United States government possesses a weak hegemony; it is always needing reinforcement, most often in the form of military presence, and carceral expansion (Camp & Kelley, 2013). However, ‘softer’ forms of imperialism are exercised, particularly through public relations and public arts.

Throughout the 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s and of course up until the contemporary moment, the US has utilised numerous methods to sabotage, assassinate, destabilise, reroute, rebound, recolonise, and influence varying governments globally to subvert progressive ideology and interrupt cohesion. These things undermine not only capitalistic goods but their ability to play the role of the feudal master or plantation owner.

In this case, diaspora and continent connection practices have been interrupted and made impossible through international violence which can be unknowingly perpetuated or coercively carried out.

Returning once more to the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists of 1956, its initiation was marked by a letter sent by W.E.B. Du Bois,

“I am not present at your meeting because the U.S. government will not give me a passport… Any American Negro travelling abroad today must either not care about Negroes or say what the State Department wishes him to say” (Baldwin, 1948, p. 54).

This demonstrated to the delegation and to further conventions that the presence of US (colonial) intelligence was also present and at the table.

This was also the case at FESTAC 77, where numerous artists and scholars were profiled by the US government, and in the case of Fela Kuti, his own government.

Kuti initially supportive of FESTAC, became increasingly critical of the event, particularly of all the new construction in Lagos and the usual accompaniment of corruption (Ikonne, 2017). As such, throughout the festival, Kuti hosted jam sessions, performances, and convenings at a personal venue, which was referred to as “the African Shrine” or the Shrine for short, on his compound, also named Kalakuta Republic. Kuti’s “counter FESTAC” was immensely popular amongst FESTAC goers and performers, international and local. However, shortly following the end of FESTAC, Kuti’s compound was raided by soldiers, which resulted in numerous injuries of Kuti’s company and perhaps most devastating, the death of his mother who was thrown from the second story of the house by soldiers. Lastly, in addition to the raid, thousands, if not one million USD was taken from Kuti, who had signed a record deal advance. “Intelligence” and government action plans often rhyme with vengeance, punishment, and suppression.

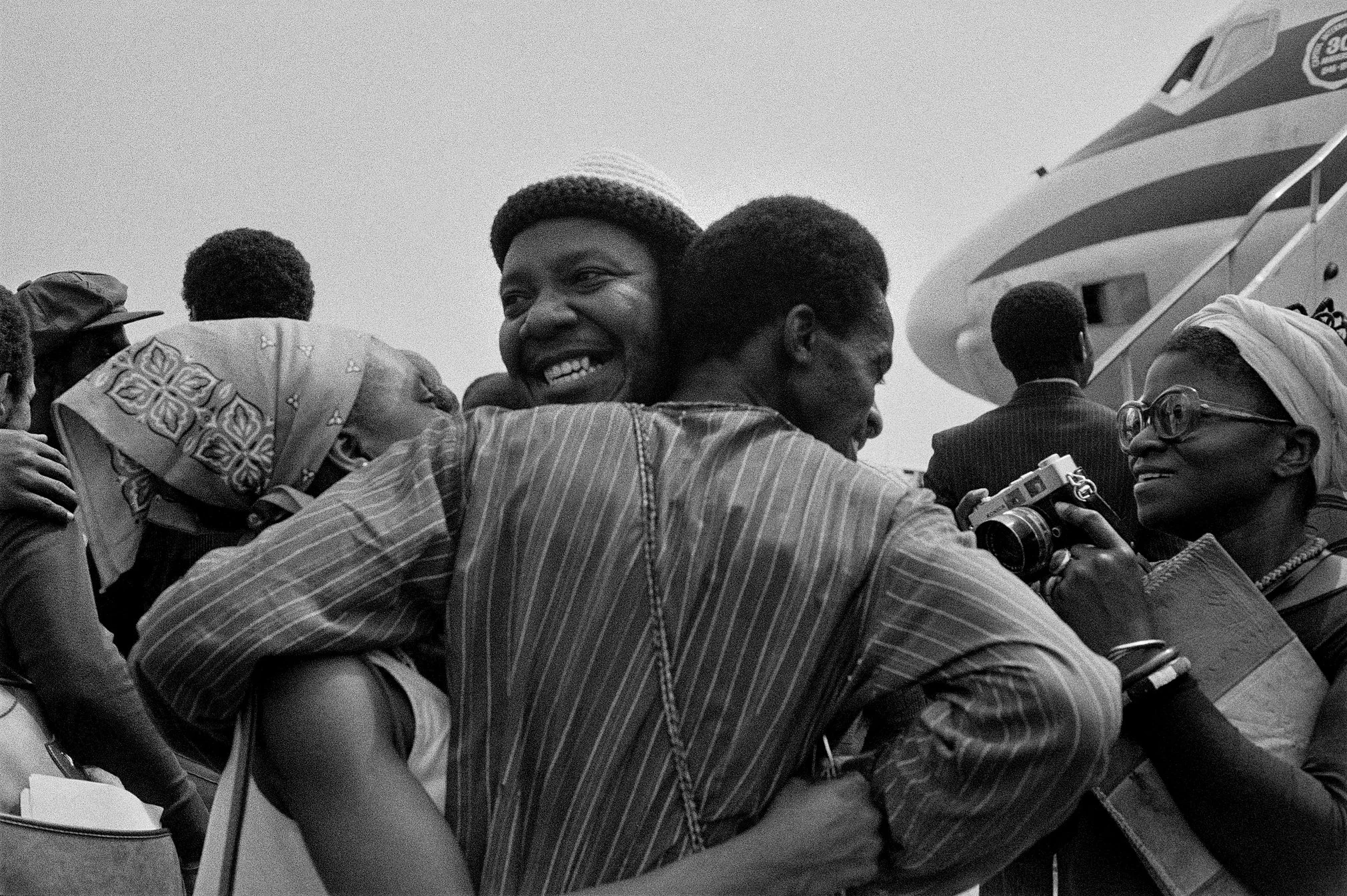

Photo: Three FESTAC photos- airport embrace, Stevie Wonder, and Fela Kuti

The US also motivated for and funded the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first president of the independent nation of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In the documentary, Soundtrack to a Coup d'Etat (Grimonprez, 2024; Elfadl, 2024), archival footage details extensive forms of manipulation, funded “opposition” parties, and to the film’s misgivings, the loose connections between the CIA and Black american jazz musicians (the CIA was doing the heavy lifting).

What the film also reifies is that the assassination was motivated not only by colonial violence but control over mineral-rich mines, an ongoing, contemporary site of destruction, violence, and displacement that is still being controlled by the private sector of the global north to build computers, phones, tablets, and much more (Amnesty International, 2023).

Additionally, the US-funded several artists to write about, travel to, and perform in varying African countries through cultural societies and journals such as the American Society of African Culture (AMSAC) and Encounter, respectively. The AMSAC sponsored artists like Langston Hughes and Nina Simone to travel to Nigeria in 1961 for programming that on paper was aimed at ameliorating relations between African-born peoples, in this case, Nigerians, and Black americans (Geerlings, 2018). Between the lines and budgeting, these kinds of events were part of what Frank Gerits (2014) refers to as the “Ideological Scramble for Africa” of the late 1950s and early 1960s. One of the major grounds of battle and infiltration was the hegemony of capitalism and the villianisation of communism. This prompted the CIA to go to varying lengths to both carry-out assassinations of leftist, Marxist, or communist-leaning leaders of newly independent nations as well as promote understanding between Black americans and citizens of African nations to further america’s familiarity and establish goodwill relationships that keep countries as a friend rather than a foe.

Further, the proliferation of debt as a colonial control tool has reified our “differences” as diasporans and those on the continent. Return is not only made impossible or bloody by international institutions and debt collectors like the IMF but also by diasporan romanticisation that lacks consideration that life feels “affordable”. Those coming with a western currency may experience a less stressful cost of living, while in June of this year, young Kenyans found themselves dying at the hands of police officers in protesting the soaring cost of living (Al Jazeera Staff, 2024; Rodney, 1972).

Missionaries, NGOs, and other ‘philanthropic’ entities further perpetuate the asymmetrical power system where certain entities are always giving out human rights, and others are always doing the receiving. This translates into a myriad of paternal power systems which are foundational to the emotional profile of colonialism: teacher and student, boss and worker; plantain overseer and chattel enslaved; NGO and underprivileged community; Messengers of Christianity and underprivileged and undereducated communities. The list goes on.

NGOs quickly established themselves as the knowledge authority on social issues that are highlighted, categorised, and deemed as social issues by said NGO. NGOs take up the lived experience of socially vulnerable people and turn that into a business model where the deemed “issue” is never solved, but the profile around it is built up, campaigned upon, documented, and submitted to funders for another 3 years of operations (Reynolds, 2022). This power relation does not have set roles, anyone can be cast, but the only immutable character is the receiver or receivers. As such, our return sometimes can wear the suit of colonialism or teacher when diasporans return with intentions that take root easily in the global north. On the other side of that same coin, infantilisation and wonder can replicate the power imbalance where there is still an extraction, still a power dynamic that cannot reconcile the two actors as whole people, but as people with roles and deliverables to share or teach.

Return interrupted by the door of no return

Photo: Leasho Johnson, The sea is another country, 2024

What I return to, most often, is Dionne Brand’s (2002) words from Map to the Door of No Return:

“I cannot go back to where I came from. It no longer exists. It should not exist.” (p.57)

Whether slavery or immigration or forced removal interrupted “us”, where we came from is not the same, by our own understanding or by the bulldozers. Or both.

Return importantly, cannot be motivated only by a desire of individual standing or collectively romanticised. Return, perhaps, shouldn't be considered so literally, or at all.

Equally, there is a murky definition of “us” and “ours” between Black and African peoples. Notwithstanding the impact of internal stratification nuanced privileges along the lines of gender, sexual identity, class standing, education, and language.

When reflecting on Aime Cesaire’s address at the Congress of 1956, Baldwin (1948) importantly noted that post-colonialism doesn’t only generate an awareness of power but an unknowing incorporation of it as well. “Cesaire’s speech left out of account one of the great effects of the colonial experience: its creation, precisely, of men like himself…He had penetrated into the heart of the great wilderness which was Europe and stolen the sacred fire. And this, which was the promise of their freedom, was also the assurance of his power.”

Those of “us” believing we are reaching “us” are also complicit in a definition that is probably exclusionary or has overshot in whom we think it may include and for what purpose: an ongoing problem and imagined answer.

The door remains open.

Black feminist interventions and Black femme sensibilities can move us through ambiguity and the constraint of one question and one answer: Where am I from? Who does that make everyone who never left, who are not looking for me?

Black radical feminist interventions (Loophole of Retreat, 2022) can teach us how to be, how to make mistakes, how to look at yourself first, how to have a quiet understanding of something, how to comfort one another because we know the fringes, we know the weight that cannot always be named but travels. We know. We know. We know. We know. We know. We know. We know beyond the script. We know beyond the cliches and talking points. We know beyond. We know the otherworldliness, the corners we’ve built and had to build. We know it's harmful there too. We know it's not paradise. We know no place on this earth is home for Black people.

Photo: Miriam Makeba and Nina Simone

However, there is something imperative and generative in space-making, and place-making. About carving out a world inside of this one, of defying what is so crudely enforced, of carrying on traditions, of fiercely seeing oneself and therefore building the capacity to see others.

Freedom is not just defined as the absence of violence, it is must contain the presence of dignity.

Connection and return must mean humanity, at no one else’s expense.

If it is possible? That may be another world.

Adams, A. (2003). Literary Pan-Africanism. In Africa and Its Significant Others (pp. 135-150).

Brill.

Aidoo, A. A. (1988). Our sister Killjoy, or, Reflections from a black-eyed squint. Longman.

Akinwotu, E. (2024). A new home for the African diaspora in Ghana stirs tensions. NPR.

https://www.npr.org/2024/02/25/1225192589/a-new-home-for-the-african

-diaspora-in-ghana-stirs-tensions

Al Jazeera Staff. (2024). Kenya on Boil as Police Fire at Anti-Tax Protesters: All You Need to

Know. Al Jazeera

www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/25/kenya-on-edge-will-anti-tax-protests-erupt-again-

amid-national-strike.

Amnesty International (2023). Forced Evictions at Industrial Cobalt and Copper Mines in the

DRC. Amnesty International

www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/09/drc-cobalt-and-copper-mining-for-

batteries-leading-to-human-rights-abuses/.

Asaah, A.H. (2021). What Is Africa to Me? or Maryse Condé’s Love-Hate Relationship with

“Ancestral Lands” Struggling with Budding Independence. Cahiers d’études africaines,

244. 875-899. http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/35784; DOI:

https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.35784

Bagneris, J. (2011). Caribbean Women And The Critique Of Empire: Beyond

Paternalistic Discourses On Colonialism. Master’s Thesis: Vanderbilt University.

https://ir.vanderbilt.edu/bitstream/handle/1803/

15016/MAThesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Baldwin, J. (1948). The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction. New York: St. Martin’s, 1985.

Brand, D. (2002). A map to the door of no return : notes to belonging (Vintage Canada ed.).

Vintage Canada.

Camp, J. T., & Kelley, R. D. G. (2013). Black Radicalism, Marxism, and Collective Memory: An

Interview with Robin D. G. Kelley. American Quarterly, 65(1), 215–230.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41809558

Elfadl, M. (2024). ‘Soundtrack to a Coup d’etat’ Review: Innovative Doc Draws a Connection

between Jazz Music and the Assassination of Patrice Lumumba. Variety,

variety.com/2024/film/reviews/soundtrack-to-a-coup-detat-review-1235937901/.

Edjabe, N. (2021). Reproducing Festac ’77: A Secret among a Family of Millions.

THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE.

thefunambulist.net/magazine/pan-africanism/reproducing-

festac-77-a-secret-among-a-family-of-millions-with-ntone-edjabe-and-kwanele-sosibo.

Fejzula, M. (2022). Gendered labour, negritude and the Black public sphere.

Historical Research, Volume 95, Issue 269, pp. 423–446,

https://doi.org/10.1093/hisres/htac008

Garvey, M. (1992). Philosophy and opinions of Marcus Garvey. New York :

Toronto : New York :Atheneum ; Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; Maxwell Macmillan

International

Geerlings, L. (2018). Performances in the theatre of the Cold War: the American Society of

African Culture and the 1961 Lagos Festival. Journal of Transatlantic Studies, 16(1),

1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794012.2018.1423601

Gerits, F. (2014). The Ideological Scramble for Africa. The US, Ghanaian, French and British

Competition for Africa’s Future, 1953–1963.

PhD diss., European University Institute, Florence.

Grimonprez, J. (2024). “Soundtrack to a Coup d'Etat”. Onomatopee Films and Warboys Films.

Hall, S. (1997). The spectacle of the 'other'. Representation: Cultural Representations and

Signifying Practices. London: Sage. pp. 223-290.

Ikonne, U. (2017). FESTAC ’77. Red Bull Music Academy Daily.

daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/05/festac-77-feature.

Isaacs, L. (2016). Maxwele Accused of Assaulting Feminist. Independent Online, IOL

www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/maxwele-accused-of-

assaulting-feminist-2005605#google_vignette.

James Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni (1971). ‘A Conversation’. Full Broadcast Video.” SOUL

[original broadcast 1971]. YouTube 2022.,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=y4OPYp4s0tc.

Loophole of Retreat (2022). Simone Leigh 2022 Venice Biennale,

simoneleighvenice2022.org/loophole-of-retreat/.

Lumières Noires (2016). Directed by Bob Swaim . France: Intermission.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-apY7hTJWNU

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

Rosen, M. (2023). Revisiting Festac ’77. Blind Magazine

www.blind-magazine.com/stories/revisiting-

festac-77-the-landmark-pan-african-festival/.

Shepperson, G. (1962). Pan-Africanism and “Pan-Africanism”: Some Historical Notes.

Phylon (1960-), 23(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.2307/274158

Staples, R. (1979). The Myth Of Black Macho: A Response To Angry Black Feminists. The

Black Scholar, 10(6/7), 24–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41163829

Morrison, T. (1987). Beloved. Chatto & Windus.

Ngugi, Mukoma Wa [@MukomaWaNgugi]. “My father @NgugiWaThiongo_ physically abused my late mother – he would beat her up. Some of my earliest memories are me going to visit her at my grandmother’s where she would seek refuge. But with that said it is the silencing of who she was that gets me. Ok- I have said it.” Twitter, March 12, 2024, https://x.com/MukomaWaNgugi/status/1767623706530992228.

Oyèwùmí, O. (1997). Colonising Bodies and Minds: Gender and Colonialism. The Invention of

Women: Making African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. University of Minnesota

Press. pp. 121 – 156.

Oyèwùmí, O. (2005). Visualizing the body: Western theories and African subjects. African

Gender Studies: A Reader. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 3-21.

Reynolds, Kim M. (2022). When Ngos Don’t Help. AMAKA.

amaka.studio/content/JMEUgVtkRwvcw4wiwnJBn.

Wahab, A. (2021). “The darker the fruit”? Homonationalism, racialized homophobia, and

neoliberal tourism in the St Lucian-US contact zone. International Feminist Journal of

Politics, 23(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2020.1758589

Wallace, M. (1979). Black macho and the myth of the superwoman. John Calder.

Xaba, M. (2013). Running & other stories. Modjaji Books.