Why Affect: Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

Shifting through my senses I recall, a protracted quietude, then a medley of crackles and fizzes. Then, “I don’t wanna foreshadow anything here, but she has not just this week, but in warm-ups today, really had a tough go.” The commentator continues while the artist reverberates their voice to sound like a pulsating echo, “momentum is really not feeling the right way for her tonight as well.” This is the voice we hear in Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi's sound installation titled Chorus, a part of Landings, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s latest exhibition at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. Chorus offers auditory senses of commentary amongst crowds clattering and competition readiness.

This aspect of Nkosi’s works — from her Gymnasium (2019-), Heroes (2012-) and the latest exhibition, Landings — to me, exercises this idea of affect theory that provides a space to understand bodily or embodied experience. An embodied experience, I think, is evident in Nkosi’s works: a space from which to think through affect theory and the affective turn. In an article in The New Yorker about literary scholar and cultural theorist Lauren Berlant’s 2011 book Cruel Optimism, journalist Hua Hsu observes in Berlant’s writings: “Everyone has heartstrings. Over time, she [Berlant] wrote, we had grown addicted to having them pulled, rather than focusing on what the pulling could accomplish by way of political change” (n.p.). The effects of this pulling on ‘heartstrings’ in Nkosi’s work can introduce a political change that begins to look at affect as a means for social and institutional transformation, as well as positive imagination.

In this probing paper, I briefly explore affect and its tenets as a novel theory. Then, I move into how affect can be read through and with Nkosi’s works, specifically her Gymnasium series by exploring gymnastics as a sport in which the Black body exists. Finally, I explore affect in terms of national identity and nationhood as well as explore affect in heroes and non-heroes[i] via Nkosi’s apt series Heroes.

The Affect

Whilst I have an interest in what affect theory and the affective turn as a recent philosophical undertaking in the humanities can do, I am also aware of how elements of affect in reference to the artist’s work agitate some tenets in my master’s research.[ii] However, I still think that Nkosi’s visual language articulates necessary social understandings of the Black ‘subject’ as suggested throughout the text. As a theory and concept, affect is specific to bodily or embodied experience. The affective turn is used to understand and/or place experience and the affective qualities that are brought upon by visual mediums (such as art) to the fore. Affect theory is used “to synthesise the body in the mind,” to go beyond a body/mind separation and indicate that the one, in fact, can influence the other. The move away from the linguistic form (i.e., the death of the author) proposes that language is not the only means to understand humans or social structures. Affect can be used as a theory to understand humans and social structures. Its turns in various fields in the humanities have meant that meaning, for affect, is multi-layered. Although related, affect is still distinct from emotion or emotions. For Brian Massumi, philosopher, and social theorist, affect precedes emotional states; it is a non-conscious experience of intensity that cannot be fully realised in language.

In affect theory, response to objects does not come from within (as, say, emotions) but begins as a pre-individual moment. In the introduction to The Affective Turn: Theorising the Social (2007), editors Patricia T. Clough with Jean Halley write, “The notion of affect: pre-individual bodily forces, linked to autonomic responses, which augment or diminish a body’s capacity to act or engage with others” (n.p.). It is probable that this likelihood of affect — through finding elements of one’s subjectivity or sovereignty in visual forms — is one of the notions on which the gaze has come to be known. In other words, in the instances when we see ourselves in the way ‘the Other other’ sees us is the affective pre-individual moment, which we seek to covert or subvert in another likeable manner. Representation, as it were, is built on subverting conditions of the gaze. It is Nkosi’s practice that allows for this affective space for black/brown individuals needing to, in a sense, re-build (or continue building) their subjective/sovereign identity.

The Sport

Team, like Ceremony and Qualifiers (2020), shows us a group of gymnasts embracing each other against an angular pale-yellow and white background. Media personnel focusing their lenses on them. Whilst being watched in this one-and-a-half metre square painting, we see the team celebrate together. Some clasp their hands to their face in disbelief, others embrace each other for their accomplishments. The shared intimacy of collectiveness and teamwork is ever so present in the work.

Whilst the sport, like any other public stage for Black bodies, is not soft on Black athletes, what makes gymnastics as an object of focus, specifically, successful is the, at once, softness and hardness of the sport. As if mimicking the conditions of Black life, at most points it is hard; at some points, it is soft too. It is this duality in conjunction with the colour use, the inherent softness of the pastel colours, that provides a soft space for realising identity.

Team, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, oil on canvas, 150 by 150cm, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

“Elite gymnastics occupies a powerful symbolic position in the public imagination — the human body performing at, and sometimes seemingly beyond, the limits of the possible. The gymnasium is a stage where dramas are enacted under a gaze of intense scrutiny. Gymnasts become actors, producing layered narratives of far-reaching metaphorical and political significance. One of the most personally affecting narratives in the recent history of the sport has been that of the precarious position of the Black body in traditionally white spaces,” explains a short text from The Africa Centre in New York, for which Nkosi was commissioned for a new wall painting in 2019. It is from this position of Black bodies in traditionally white spaces that I will segue into Patricia T. Clough’s 2008 journal article The Affective Turn: Political Economy, Biomedia and Bodies. Although a particularly dense text, I believe that Clough, as a key introduction to the concept of ‘affect,’ proves useful. Clough begins her article with an invitation to the turn to affect (1) which was employed by critical theorists and cultural critics as a move away from the limitations of poststructuralism and deconstruction. Post-structuralism, which emphasised plurality and a deferral of requiring meaning, and deconstruction, which focused on texts as such without (the consideration of) the author’s intention(s) and the limitations or impossibilities of interpretation (Clough, 1). With this invitation to turn to affect, Clough employs Rei Terada’s argument that “the turn to affect and emotion extended discussions about culture, subjectivity, identity and bodies” (1). Furthermore, Clough asserts that affect, along with post-structuralism and deconstruction, points to “the subject’s discontinuity with itself, a discontinuity of the subject’s conscious experience with the non-intentionality of emotion and affect” (1). With the emphasis on formalist approaches to understanding socio-cultural forms, we have simply, maybe, lost touch by being preoccupied with tedious tasks of pluralism, deferral of meaning, killing the author and the limitations of interpretation. We have, perhaps, not considered how we are affected.

In The Evidence of Experience, social science professor Joan W. Scott asserts “that the narrative can be said to determine the evidence as much as the evidence determines the narrative” (776). Scott affirms that the experience of an individual subject is truer than the perception of the universality — and even invisibility — of certain histories. She adds further that “the evidence of experience then becomes evidence for the fact of difference” (Scott, 777). Would it then be permissible to think of affect as the preconscious moment towards the conscious evidence of experience? Along with affect and experience as mechanisms of being in the world, can these methods in which we think closer about culture, subjectivity, identity, and bodies be worthwhile?

Our sovereignty lays out what is fundamental about our experience — what is true and evident to us. Our sovereignty is further endorsed by narratives (or, in this case, a visual language). Thus, a turn to affect is interesting in order to extend discussions about lived experiences and abstracts[iii] like race, gender, class, and nationality. With this, we can explore the possibilities in relation to Nkosi's Heroes and Gymnasium series.

Reverting to Clough’s article, she introduces the forging of a new body, the biomediated[iv] body, a body and its affectivity (2). I am more interested in this new body, the biomediated body, in terms of non-virtual mediation or mediation without technology. This mediation is visual practice, or artistic practice. This way of thinking may be appropriate to understand how Clough positions the biomediated body in terms of Brian Massumi’s thoughts about how affect links to the philosophical conceptualisation of the virtual, ‘visceral perception.’ For Massumi the turn to affect “is about opening the body to its indeterminacy…to define affect in terms of its autonomy from conscious perception and language, as well as emotion” (Clough, 3). Nkosi’s Gymnasium series, in some essence, speaks to this idea of the affect, the general affective quality of art that (although the perception of art can be subjective) is a recurring theme in artistic practices. Clough’s consistent use of Brian Massumi’s 2002 Parables for the Virtual — which looks at the body and various forms of media as cultural formations that operate on multiple registers of sensation beyond the reach of reading techniques — proves useful for how the term ‘affect’ can travel across disciplines.

A specific point about affect that concerns experience lies in Determinism: The Phenomenology of African Female Existence by Bibi Bakare-Yusuf. Bakare-Yusuf suggests an African Feminist Theory that must specify and analyse “how our lives intersect with a plurality of power formations, historical encounters and blockages that show our experiences across time and space” (8). Additionally, there is a need to clarify how embodiment produces and affects our experiences in the world (Bakare-Yusuf, 9). Bakare-Yusuf speaks exclusively to the phenomenology of African women on the African continent. Whilst Nkosi is a South African artist, the essence of the Gymnasium series is immediately implicated in the recent record and championship triumphs of African American gymnasts Simone Biles, Gabby Douglas, and others. The phenomenology of a Black women’s existence in this gymnastic world as a racialised institution (as will be outlined in the following paragraph) attempts to distort and probe “the ‘natural attitude’ or commonsensical or normative modes of description” (Bakare-Yusuf, 16).

While Clough proves useful for the understanding of affect, Nicole R. Fleetwood places more emphasis on visual culture, language and culture that is valued. Fleetwood’s book Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness is a study of black visuality and performance (2). Nkosi, in an interview with the Document Journal, reveals the elitist and white supremacist history of gymnastics. Speaking about Simone Biles, an African American woman gymnast and the world’s most decorated gymnast, Nkosi further relates that Niels Bukh[v], promoter of gymnastics, used the sport as a system for white supremacy, specifically as a method to promote the notion of the ‘ubermensch’ aligning with Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party (Rosen, n.p.). Moreover, Nkosi speaks of her role as an artist and Biles’ distortion of the norm as follows: who can be a world gymnast championship while performing and being visible in spaces deemed historically white and, in most instances, still upheld by white superiority?

Champion (2020), a one-and-a-half-metre square oil painting, shows us a gymnast in a pale-yellow leotard walking back towards the sidelines. A few people are sitting, but their presence does not bring on anxiety; instead, it aids a quiet calm, a quiet congratulations, and quiet delight. We comfortably walk into the affective space these characters have created, their arms and legs folded gently. Another claps with their body directed to us as we move through the space. It reminds me of my competitive swimming days where a calm congratulatory note from my mum awaits me.

Champion, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, oil on canvas, 150 by 150cm, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

In her introduction to her book, Fleetwood employs Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing as an examination of her thought process throughout the introduction of the book. She asserts that “the affective power of certain instantiations in black cultural production to generate a response to what is racialised as black: subject, matter, space, experience” (Fleetwood, 2). Furthermore, she describes her watching and subsequent sitting with Lee’s film as “being moved by black visuality” (Fleetwood, 3). It is precisely the italicisation of the word ‘moved’ that suggests some type of emotion that cannot be named. This emotion — this ‘moving’ or being ‘moved’ by black visuality — speaks to something within her: affect to experience. Although there may be an implicating reference to Simone Biles in looking at Nkosi’s paintings, there are no inherent distinguishable features of the gymnasts and judges. Yet, without distinguishable features, one can identify with Black bodies; this is the affective power that Fleetwood mentions, or the politics of affect as written in Nigel Thrift’s Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect.

I turn to Amplitude (2020). According to the Apple Dictionary, the origin for the word comes from Latin's amplitudo, from amplus which is 'large and abundant’ and 'in the senses,’ a mid-16th century understanding of 'physical extent' and ‘grandeur.' The gymnast is mid-air, mid-choreography, almost flying. We see no other human presence except background highlights of a room. The image this painting depicts is so surreal that it feels far afield from the competition’s noise, grading, and judging. It is a quiet moment, but a precarious one. It is unknown how the gymnast lands or finishes, how they will be graded, how the audience will cheer or not cheer, how their team will celebrate with them. Suspended in a reality so obscure, yet so familiar, this painting creates a moment in which we ponder failure and success, how we move or how we do not move, our sovereignty whilst being watched or surveilled. All these affective breadths are stated in one painting, so eloquently, by a gymnast shielding themselves.

Amplitude, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, oil on canvas, 100 by 116cm, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Photography by Nina Lieska.

The Heroes

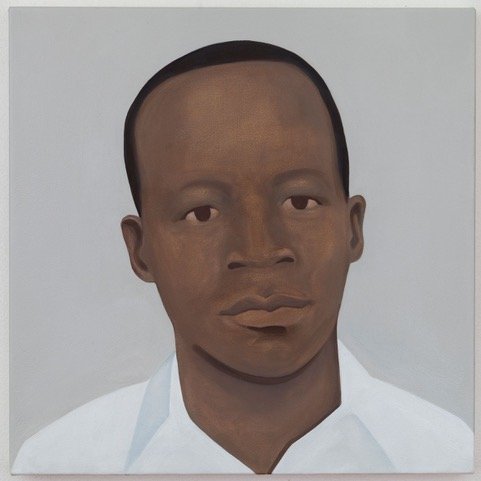

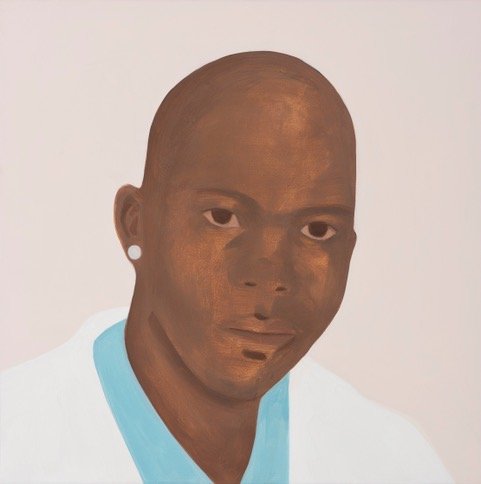

I would like to move on to Nkosi’s Heroes series to frame Fleetwood’s writing on iconicity and non-iconicity, affective power, and collective attachment. Walt Hunter, in his interview with Nkosi for the online ASAP Journal writes about how Nkosi “confronts the viewer with historical figures from Bessie Head to Winnie Mandela who occupy oblique positions with respect to the nationalist mythologies of the hero” (n.p.). Nkosi speaks about the series as an “ongoing personal gesture of remembering and memorialising” and also attempts to interrogate history: “who writes history, who gets to choose the heroes and who gets left out of history.” Nkosi’s Heroes speaks both to the icon, which Fleetwood describes as producing “affective responses in audiences by ‘sticking’ the thing or person signified to normative codes, meaning and values, what Hariman and Lucaites refer to as the ‘iconic affect’” (34). Heroes also spells to non-iconicity, which Fleetwood describes as “an aesthetic and theoretical position that lessens the weight placed on the black visual to do so much. It is a movement away from the singularity and significance placed on instantiations of blackness to resolve that which cannot be resolved” (9). Alternatively, we can think of portraits like Hani, Head, Mahlangu (After Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu), Upright Man (After Thomas Sankara), and Mother (after Winnie Mandela) as heroes (i.e., the subjects of the portraits identified as icons in the historical narrative) in contrast to portraits like Translator (After the one who may have been called !Oroõas, misnamed Krotoa by the Dutch Settlers), Mido (After Mido Macia), Anene (After Anene Booysen), and Sibolile (After Sibolile Nkosi)[vi] as non-heroes (i.e., subjects not known in the larger historical narrative, subjects visible only to certain sections of society).

Fleetwood asserts of the affective power of the circulation of Blackness (6), the Black body, and the meanings that get attached to and circulate it (7), further positioning this notion of collective attachment. Fleetwood uses Lauren Berlant’s concept of ‘collective attachment’ as follows: “In theorising affect and the sociality of emotions, Lauren Berlant uses the phrase ‘collective attachment’ and defines this concept as a form of optimism in how emotions can bring individuals together” (10). Further to this point, not only does Nkosi’s Heroes series act as a counter visual archive (Fleetwood, 69), it also serves as an investigation into what is personal to Nkosi in terms of representation. Nkosi seeks to memorialise local histories by disrupting and upholding notions of the hero specific to the South African geohistory.

Mahlangu (After Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu), Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, oil on canvas, 50 by 50cm, 2016. Courtesy the artist.

Moreover, Nkosi uses 50 cm by 50 cm canvases for all the Heroes paintings as reminiscent of standard identification photos (although, typically South African identity photographs are rectangular rather than square). Nkosi describes this gesture as follows “Power collapses in the ID photo. We are all standardised within it…There is something intensely democratic about the format” (Hunter, n.p.). So, heroes and non-heroes are treated the same within the series: standardised formats, similar titles, similar colour palettes and backgrounds. Although, there is a purposeful tension between the heroes and non-heroes the series reveals “the affective power of black representational practices” (Fleetwood, 10) as “black iconicity serves as a site for black audiences and the nation to gather around the seeing of blackness” (Fleetwood, 10).

Simultaneously, Nkosi’s portraits of these heroes and non-heroes suggest ways to subvert Fleetwood’s statement that “the icon is a fixed image so immersed in rehearsed narratives that it replaces the need for narrative unfolding” (46). Nkosi, in her interview with the ASAP Journal, recounts the beginnings of the Heroes series:

I was looking through the money in my wallet and started thinking about the fact that all my bills (10, 20, 50), all had Nelson Mandela’s portrait on them…It got me thinking about the ways in which we construct history in South Africa through the memorialisation of certain figures. It is clear that who gets memorialised is a political issue — and one that always has the consolidation of power as at least one of its aims. Looking back, the idea to paint portraits was seeded in that moment: I realised that I wanted to make a gesture towards expanding our very myopic historical narrative(s) — (Hunter, n.p.)

The practice of including non-heroes seeks to subvert the notion of who can become an icon and why. There are several alternative instances in art history wherein individuals are memorialised including Sue Williamson’s For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990)[vii], and Fayum mummy portraits[viii].

For the mere sensation of affect — by way of identifying with the subject of the portrait and their lived experiences — the viewer can disregard the fixity of power inherent in icons and heroes. The difference between the treatment of icons and non-icons lies in the affective power of collective attachment and memory: certain figures speak to the entire echo chamber of a nation and are, therefore, an automatic association for those who comprise the nation. However, the Heroes series urges us to consider those on the periphery of iconicity.

Mido (After Mido Macia), Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, oil on canvas, 50 by 50cm, 2016. Courtesy the artist.

Tina M. Campt in her 2017 book Listening to Images, describes the act of ‘listening to images’ as an intervention that is at “once a description and a method” (5). By listening, we are given access to the “affective registers through which these images enunciate alternate accounts of their subjects” (Campt, 5).

Nkosi’s painting series Gymnasium and Heroes are examples of how we can consider affect as a methodology for understanding notions of history, experience, sensation, and bodies in varying spaces in which we the subjects of visual practice move. With the array of affective responses to visual material and visual culture, how can we begin to consider how the artists' intentions may align with critical and analytical ways of thinking and writing about visual practice? It is the call to the affective turn and non-linguistic affects that is enticing to consider. Therefore, affect is necessary, especially so, considering how effective it has been listening to and looking at Nkosi’s Gymnasium and Heroes series.

-

-

-

-

Bibliography

Bakare-Yusuf, Bibi. “Determinism: The Phenomenology of African Female Existence.” Feminist Africa, vol. 2, pp. 8-24.

Campt, Tina M. “Listening to Images.” Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Clough, Patricia T. “The Affective Turn: Political Economy, Biomedia and Bodies.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 25, no. 1, 2008, pp.1-22.

Clough, Patricia T & Halley, J. "The Affective Turn: Theorising the Social”. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017. https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-affective-turn

Fleetwood, Nicole R. “Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness.” Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Hsu, Hua. “Affect Theory and the New Age of Anxiety: How Lauren Berlant’s cultural criticism predicted the Trumping of politics.” The New Yorker. 18 March 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/03/25/affect-theory-and-the-new-age-of-anxiety.

Hunter, Walt. “The History of Heroes Still to Come: An Interview with Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi.” ASAP Journal. 25 June 2018. http://asapjournal.com/the-history-of-heroes-still-to-come-aninterview-with-thenjiwe-niki-nkosi/ .

No Author. “Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi: Gymnasium.” The Africa Centre. 06 March 2020. https://www.theafricacenter.org/event-thenjiwe/ .

Rosen, Miss. “Artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi reveals-and defies-the white supremacist underpinnings of elite gymnastics.” Document Journal. 07 November 2019. https://www.documentjournal.com/2019/11/artist-thenjiwe-niki-nkosi-reveals-and-defies-the-white-supremacist-underpinnings-ofelite-gymnastics/ .

Scott, Joan W. “The Evidence of Experience.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 17, no. 4, Summer 1991, pp. 773-797.

Thrift, Nigel. “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, vol. 86, no. 1 (Special Issue: The Political Challenge of Relational Space), 2004, pp. 57-78.

Endnotes

[i] Or rather, as public heroes and private heroes, as suggested by Dr Alison Kearney. I think this is a more resolved way in which to reframe how I use heroes and non-heroes. For the flow of the text, I will continue using the terms heroes and non-heroes. This distinction is apt in order to agitate who exactly gets to be remembered on a national level and why this memorialisation (publicity) happens on a large scale. Without sounding reductive, any sovereign could, can and is a hero, but they are not memorialised within the public sphere. By collapsing the two distinct spheres Nkosi shows us that they are indeed one, as described in The Heroes section of this paper.

[ii] In “Sovereignty, Fugitivity and ‘Post-Blackness’: An Exploration of Dineo Seshee Bopape and Ana Mendieta’s Terra Works” (2021), I argue for how sovereignty and fugitivity, as concepts, provide alternatives means of exploring black life without further subjugating black life to gazes and consumption. While not entirely a response to black representation (or social realism), and not necessarily against black representation in artistic practices, rather I offer a way to present black life in a way that allows black bodies breathing space and rest whilst agitating the abstracts against which our bodies are further violated.

[iii] Real-but-abstract: race as possibilities and race as potential; as a concept that is abstract as well as real; abstract possibilities, as per Lauren Berlant.

[iv] The biomediated body is a body subjective to the affective.

[v] Niels Buhk was a Danish gymnast and educator whose ’primitive gymnastics’ became popular in Germany. Bukh expressed his alignment to the German national socialist cause to promote the health of the Aryan race through gymnastics. As such, gymnastics as a sport has within it an association with fascist ideology. For Nkosi, “Ideology is at work in this sport. Gymnastics has been used as a tool of propaganda, of control, of patriarchy and of nationalism. Defining what bodies should look like, what perfection is, what the ideal human is. And here we are now, witnessing the dominance of Simone Biles. And now that ’uber human’ is a young Black woman.” (Nkosi, “Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi; Gymnasium” [2020], pg. 19). Interestingly, those words or tools of fascism — propaganda, control, patriarchy and nationalism — can be viewed within the frame of the affective turn. How does Nkosi’s work begin to disrupt the affective qualities that those systems contain within? How do those affective qualities extend or consume those who are living in fascist states and communities?

[vi] Sibolile is a portrait of the artist’s great-grandmother and former ‘domestic’ worker for Paul Kruger, president of apartheid South Africa.

[vii] A photographic installation work that memorialises a passbook (an identity document that Black South Africans carried to move within predominantly white areas, major cities and for employment) belonging to Ngithando John Ngesi, a dock worker who carried the pass for thirty years.

[viii] The panel paintings of upper-class Roman Egyptians retained a life-like portrait of said subjects, memorialising those in the afterlife.